Michele Tocca | Poca Notte: curated by Davide Ferri

z2o Sara Zanin is pleased to present, on Thursday May 9th, Poca notte, the first solo exhibition in the gallery by Michele Tocca (Subiaco, 1983), curated by Davide Ferri.

Scroll down for the Italian version

Footsteps

by Davide Ferri

A couple of times a week I get up at four or five in the morning to go to the academy, either in Bologna or Macerata. And as I ride the train, still dark outside, maybe with my notebook just opened to prepare my lecture (or if I’m driving and stop at a service station for a second cup of coffee), I sometimes get the urge to text Michele. Let me confess that I rarely have anything urgent to tell him. It’s kind of a game we play. I just do it to see if he’s already up as well. We laugh about our tendency to get up so early in the morning. It seems to make the night less long. I just write: “Good morning, Mike”. And no more than few seconds later, every time, he answers “G’morning, Ferri”.

Why do I even mention this? Because by means of its title and every painting exhibited, Poca notte [Not much night], Michele Tocca’s first solo show at Galleria Sara Zanin, seems to reference a specific moment in the day that corresponds to a particular condition of seeing, an intermediate time between night and day, when the earliest glimmers and lights open up vision, first faintly, then resonating in the darkness. “It’s the ideal dimension of the almost-nothing”—Michele once wrote—“in which ‘everything’ is still to be gained, stolen, even distant light, rays, and a flash that recalls lightning but isn’t. Then dawn comes, that stupid sensation of crescendo, with this beautiful untranslatable English word: incremental.”

Michele surely gave some serious thought to the word “incremental”. Is there an equally appropriate word in Italian for this condition of seeing, this gradual, velvety emanation of light that the exhibition wants us to experience? Maybe not. On various occasions over the past few months we sat in his studio racking our brains for an Italian word or expression that describes the variations and movements of light with the same precision.

We finally resorted to a poet, Giovanni Pascoli, and his renowned antithesis our school kids study: “apparì sparì,” which, read in all one breath, says everything about a burst of lightning: “....appeared quick disappeared in one spark.”[1]. I don’t feel the need to go to great length explaining why, but I think this show, even Tocca’s work in general, has something distinctly “Pascolian” about it.

Strange but true. As Cesare Garboli explains in Trenta poesie famigliari di Giovanni Pascoli, a trenchant essay (1985) that takes another look at the poet’s private life, Pascoli’s poetry arises from an ineffable painful mystery hidden by the walls of the family home.

Poca notte is, first and foremost, a path of the light. It starts, ideally, with the largest of the works on display, The window (a bit of night) in which nine overlapping paintings configure a black surface with the minimal indication of depth given by the picture frame/window frame painted around each one, a "quasi-monochrome," in which each work’s layer of black paint has a flowing, animated quality. Add ambiguous to that. What causes, for example, those irregular veils or rifts of white that seem to expand and contract in each frame? Is it water vapor, dirt on the glass, reflections, light and shadow of landscape only vaguely perceptible from inside? Or is it all these things together? Likewise, what are those thin, irregular lines that furrow the top of one of the window’s panes? Cracks in the glass? Cobwebs? Glare from outside?

Looking at that painting, others of the past with windows that do not show any depth or open out into a space of full vision due to the way they are painted inevitably come to mind: The Balcony by Edouard Manet (1868), for example, with that window in the background that frames an interior, a dark, pasty backdrop from which fleeting indications of things and figures living inside emerge (a waiter bears a tray, crockery on shelves, paintings on the walls); Open Window, Collioure by Henri Matisse (1914),–painted by the artist just before the things outside ‘the whole world’ in this case, was about to go up in flames–an abstract painting at heart, a black monochrome, with blue and white bands and backgrounds at the sides that are really shutters and blinds; in particular, various paintings by Dutch painter, Jacob Vrel that always show the same corner of the room, with the same black window in the background that happens to look a lot like Tocca’s and on whose surface the reflections of what is inside can be confused with the presences outside.

The ability to make the boundaries between things inside and outside porous, thus contaminating each other, is an integral part of Tocca’s painting and images that is particularly evident in the “portraits” presented here. I use quotation marks because it’s worth remembering that Tocca paints from life in the presence of things and sometimes in 1:1 scale without touching things up later, objects seen in a domestic setting that may also extend to the landing and stairwell, the parts of the house most subject to stress from outdoors. And it is the objects themselves that bring these two dimensions, the inside and the outside, into relationship: worn shoes I once called "shoe-landscapes" deformed equally by the human body, the earth, and changes in the weather; a rain-soaked sweater (hung on the back of a chair) that the damp night air has yet to dry completely, or the broom that sweeps up the dust and dirt that enter the house from the landscape outside on the soles of shoes and through open windows.

Getting back to the path of light. It started with The window (a bit of night) and continues with 9 am, it melts, a landscape filtered through condensate formed on the glass. The cloudiness on the window blends with the mistiness outside (clouds, mist) and establishes a continuous vision between inside and outside that leads to By dawn (Violet), a small painting isolated on a wall in which the purple light that appears before dawn is a presage of light’s later unstoppable expansion. By dawn (Violet) also suggests growth (an increment, precisely) that’s clearly capable of expanding on the wall and into the space around it, a luminous movement born of blackness, not only of the night, but also of the brushstrokes that summarily describe the frame of the pair of glasses that frames the image.

There’s what I would call an unprecedented aspect of Tocca’s work: a common thread running through the show, black, (in contrast with the path traced by light), because if I had to think of a color that has

always appeared in his painting, it would be brown, a singular brown, however, one that succeeds in providing his paintings with a sort of “muddiness” and vibrant brightness at the same time.

In Poca notte, every vision of light seems instead to start from blackness or be framed by it, such as in By dawn (Violet) but also in the smaller paintings titled Ray opposite and Before they wake up, visions seen through binoculars of houses dotting the landscape nearby, still fast asleep, and in Light lighting, giving a view of sky between a mountain ridge and the edge of an umbrella (black) glimpsed while walking on a rainy morning.

This show also features red, a red I’d never really seen before in any of his paintings (Too late) but which appears in that sweater hung on a frame in the last painting the visitor sees before leaving the show on the wall across from the entrance.

***

When you get up so very early in the morning and wander around the house, you’ve got to pay close attention to the sound of your footsteps: the silence makes them louder and arouse those still sleeping. The point I wish to make here is that I think I hear pre-dawn footsteps in Poca notte, the footsteps of someone unseen wandering among the things in the paintings. But Tocca doesn’t paint figures (in the sense of bodies and people), a figure appears, if at all, by contact or contagion on the surface of the things he portrays. But as you look at the works in

Poca notte that refer so precisely to a limited time and space, you can hear this wandering down a hallway, this stopping to look at the corner of a room, or this gazing out onto the landing of the house in the dark. And the sound of these movements, these footsteps, so to speak, makes you wonder if they aren’t really your own.

[1] “stark white in the dumb wake of chaos a home/appeared quick disappeared in one/spark” (“bianca bianca nel tacito tumulto/una casa apparì sparì d’un tratto”). T. Silverman, M. Della Putta Johnston, Selected Poems by Giovanni Pascoli (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019) 56-57.

Translated by Craig Allen

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I passi

di Davide Ferri

Un paio di volte alla settimana mi alzo alle quattro o alle cinque per andare in accademia, a Bologna o a Macerata. E mentre sono in treno, quando fuori è ancora buio e magari ho appena aperto il quaderno degli appunti per ripassare la lezione (oppure, se viaggio in auto, quando sono in autogrill, per un secondo caffè), può venirmi in mente di scrivere un messaggio a Michele. Devo confessare che non ho quasi mai niente di veramente urgente da dirgli. È una specie di gioco tra noi, lo faccio per vedere se anche lui è già in piedi, perché spesso scherziamo sulla nostra tendenza ad alzarci presto la mattina, molto presto, ad accorciare la notte. Così mi limito a salutarlo: “Buongiorno Mike”. E dopo qualche secondo – ogni volta, puntualmente: “Giorno Ferri”, mi risponde lui.

Perché racconto queste cose? Perché Poca notte, la prima personale di Michele Tocca nel nuovo spazio della galleria Sara Zanin, sembra rinviare, attraverso il titolo e ogni dipinto in mostra, a un momento della giornata, a cui corrisponde una particolare condizione del vedere. Un tempo intermedio tra notte e giorno, quando i primi bagliori e accensioni di luce aprono la visione, prima fiocamente, per poi risuonare nel buio. “È la dimensione ideale del quasi niente – ha scritto una volta Michele – dove 'tutto' è ancora da guadagnare, rubare - anche la luce lontana, i raggi, un mezzo lampo che lampo non è. Poi arriva l'alba, quella sensazione di stupido crescendo, con questa parola inglese bellissima che in italiano non esiste: incremental.”

Su questo “incremental”, debbo dire, Michele ha rimuginato parecchio. Esiste in italiano una parola altrettanto bella che condensi il senso di questa condizione del vedere, di questa graduale, felpata crescita di luce che la mostra vuole raccontare? Forse no, non esiste. Qualche volta, incontrandoci in studio nei mesi scorsi, siamo andati in cerca di parole ed espressioni italiane che descrivano con la stessa precisione le variazioni e i movimenti della luce. E ci è venuta in mente, tra le altre cose, quell’antitesi pascoliana che si commenta a scuola, “apparì sparì”, che, letta d’un fiato, dice tutto sull’irrompere di un lampo. Piccola parentesi: ora non voglio mettermi a spiegare diffusamente perché credo che questa mostra, e forse in generale tutto il lavoro di Tocca, abbia un carattere pascoliano. Ma vi giuro che è così. La poesia di Pascoli, lo spiega bene Cesare Garboli in quel bellissimo saggio scritto nel 1985, Trenta poesie famigliari di Giovanni Pascoli, che guarda una volta di più al mondo privato del poeta, nasce da un ineffabile, doloroso mistero nascosto tra le mura domestiche.

Poca notte è, innanzitutto, un percorso della luce. Che parte, idealmente, dal più grande dei lavori in mostra, La finestra (poca notte), composto da nove dipinti che, accostati e disposti su tre file, configurano una superficie nera con una minima indicazione di profondità, data dalla cornice/montante (della finestra) dipinta lungo i bordi di ogni singolo lavoro. Un “quasi monocromo”, dove lo strato di pittura nera di ogni pezzo ha una qualità magmatica e movimentata. E aggiungerei: ambigua. Che cosa provoca, ad esempio, quelle irregolari velature/sporcature di bianco che sembrano dilatarsi e contrarsi in ogni riquadro? Vapori, sporcizia del vetro e riverberi del paesaggio, ombre e luci, che si possono percepire solo sommariamente dall’interno? Oppure tutte queste cose insieme? E allo stesso modo che cosa sono quelle linee sottili e irregolari che solcano la parte alta di uno dei riquadri che compongono la finestra? Fratture del vetro? Ragnatele? Bagliori che provengono da fuori?

Se guardo quel lavoro, inoltre, mi vengono in mente, inevitabilmente, alcuni quadri del passato che rappresentano finestre; cioè mi vengono in mente quelle finestre che, per come sono dipinte, non si aprono alla profondità e a uno spazio di piena visibilità: Il Balcone di Edouard Manet (1868), ad esempio, con quella finestra in secondo piano che incornicia un interno, uno sfondo oscuro e pastoso da cui affiorano fugaci indicazioni a cose e figure che lo abitano (un cameriere che regge un vassoio, vasellame su mensole e quadri alla parete); Porta-finestra a Collioure di Henri Matisse (1914) – dipinto dall’artista poco prima che il fuori, il ‘mondo tutto’ in questo caso, fosse sul punto di andare in fiamme –, in fondo un brano di pittura astratta, un monocromo nero, con bande e campiture azzurre e bianche ai lati che sono imposte e persiane. E soprattutto diversi dipinti del pittore olandese Jacob Vrel, che mostrano sempre lo stesso angolo di stanza, con la stessa finestra nera sullo sfondo che somiglia molto a quella di Tocca, sulla cui superficie i riflessi di ciò che è all’interno possono confondersi con le presenze del fuori.

La stessa capacità di rendere porosi i confini tra dentro e fuori, di contaminarli reciprocamente, appartiene alla pittura e alle immagini di Tocca. E ancor più ai pezzi di questa mostra, che sono ritratti – sì ho detto ritratti, e forse conviene ripetere una volta ancora che Tocca dipinge i suoi soggetti dal vivo, talvolta in scala 1:1, lavorando in presenza delle cose e senza ritocchi a posteriori – di oggetti visti in uno spazio domestico che può allargarsi anche al pianerottolo e al vano scale, cioè a quelle parti della casa più sottoposte alle sollecitazioni del fuori. E sono gli stessi oggetti a far incontrare queste due dimensioni, il dentro e il fuori: le scarpe usate, che una volta ho chiamato “scarpe-paesaggio”, le cui deformità sono provocate allo stesso modo dal corpo, dalla terra, e dai cambiamenti atmosferici; una maglia bagnata di pioggia (e stesa sullo schienale di una sedia), che l’aria della notte, con la sua umidità, non è riuscita ad asciugare del tutto; la scopa che raccoglie impurità e sporcizie che, all’interno della casa, vengono anche dalle suole delle scarpe e dalle finestre aperte, dunque dal paesaggio.

Torniamo al percorso della luce: inizia con La finestra (poca notte) e prosegue con h 9, si scioglie, un paesaggio visto attraverso i vapori che si depositano sul vetro – vapori interni che si confondono con quelli esterni (nuvole e coaguli atmosferici) a stabilire una continuità di visione tra dentro e fuori. E arriva idealmente a Entro l’alba (viola), un piccolo dipinto isolato su una parete, al cui interno il viola che colora il cielo descrive il riverbero della luce dell’alba, il primissimo della sua inarrestabile espansione. Entro l’alba (viola), inoltre,suggerisce una crescita (un incremento, appunto) in grado di dilatarsi sul muro e nello spazio circostante, un movimento luminoso che parte dal nero, non solo della notte, ma anche quello delle pennellate che descrivono sommariamente la montatura di un paio di occhiali che incornicia l’immagine.

È un aspetto che definirei inedito del lavoro di Tocca: una linea, interna a questa mostra, tracciata dal colore nero (che fa da contraltare a quella tracciata dalla luce), perché se penso a uno dei colori che ha sempre connotato la pittura dell’artista direi che è il marrone, un marrone non ordinario che genera sempre, di fronte ai suoi dipinti, un’impressione di “fangosità” e al contempo di vibratile lucentezza. In Poca notte ogni visione di luce sembra invece partire dal nero, o essere incorniciata dal nero. È così per Entro l’alba (viola), ma anche per i piccoli dipinti dal titolo Raggio di rimpetto e Prima che si sveglino, visioni dal binocolo di case che punteggiano il paesaggio degli immediati dintorni, ancora addormentate; e per Come un lampo, porzione di cielo vista tra una montagna e il lembo di un ombrello (nero), durante una camminata in una mattina piovosa.

E in questa mostra appare anche il rosso, un rosso che davvero non avevo mai visto in un dipinto di Tocca (Troppo tardi), con quel maglione appoggiato a un telaio, che è l’ultimo quadro che il visitatore vede prima di andarsene, sulla parete accanto all’ingresso.

***

La mattina, quando ti alzi molto presto e ti aggiri per casa, devi fare attenzione soprattutto al rumore dei passi, che nel silenzio possono risuonare e svegliare le persone che ancora dormono. Ecco, il punto è che in Poca notte a me sembra di sentire un rumore di passi. Mi riferisco ai passi di una figura che, anche se non appare, sembra aggirarsi tra le cose rappresentate nei dipinti. Voglio dire: Tocca non dipinge figure (nel senso di un corpo, una persona; questa figura appare semmai, per contatto o per contagio, sulla superficie delle cose che ritrae). Ma mentre guardi i lavori di Poca notte, che rinviano così precisamente a un tempo e uno spazio delimitato, la senti aggirarsi in corridoio, fermarsi a guardare l’angolo di una stanza, o affacciarsi sul pianerottolo di casa, nel buio. E il rumore dei suoi movimenti, dei suoi passi, appunto, finisci per confonderlo con quello dei tuoi.

-

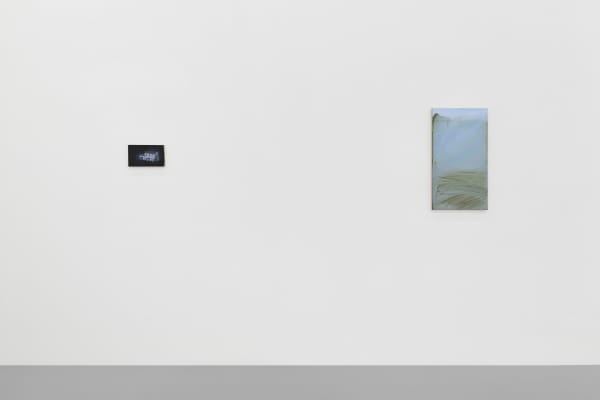

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni -

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Roberto Apa

-

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni

-

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni -

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni -

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Roberto Apa

-

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Roberto Apa

-

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Roberto Apa

-

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Roberto Apa

-

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Roberto Apa

-

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni -

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni

Installation View, Michele Tocca | Poca Notte, curated by Davide Ferri, 2024, z2o Sara Zanin | Ph. Dario Lasagni

-

The window (a bit of night), 2024, oil on linen, cm 150 x 150 overall, cm 50 x 50 each (nine pieces). Ph. Dario Lasagni

The window (a bit of night), 2024, oil on linen, cm 150 x 150 overall, cm 50 x 50 each (nine pieces). Ph. Dario Lasagni -

The window (a bit of night), detail, 2024, oil on linen, cm 50 x 50 each. Ph. Dario Lasagni

The window (a bit of night), detail, 2024, oil on linen, cm 50 x 50 each. Ph. Dario Lasagni -

Doorway broom, 2024, oil and dust on linen, cm 20 x 45. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

Doorway broom, 2024, oil and dust on linen, cm 20 x 45. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

Before they wake up, 2024, oil on linen, cm 14,5 x 25,5. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

Before they wake up, 2024, oil on linen, cm 14,5 x 25,5. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

9 am, it melts, 2024, oil on linen, cm 74 x 40. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

9 am, it melts, 2024, oil on linen, cm 74 x 40. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

The dirty shoes remain, 2024, oil on linen, cm 20 x 40. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

The dirty shoes remain, 2024, oil on linen, cm 20 x 40. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

Too early, 2024, oil on linen, cm 80 x 45. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

Too early, 2024, oil on linen, cm 80 x 45. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

Like lighting, 2024, oil on linen, cm 45 x 85. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

Like lighting, 2024, oil on linen, cm 45 x 85. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

A little flare, 2024, oil on linen, cm 26 x 16. Ph. Dario Lasagni

A little flare, 2024, oil on linen, cm 26 x 16. Ph. Dario Lasagni -

Yesterday's news, 2024, oil on linen, cm 35 x 40. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

Yesterday's news, 2024, oil on linen, cm 35 x 40. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

Ray opposite, 2024, oil on linen, cm 17 x 19. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

Ray opposite, 2024, oil on linen, cm 17 x 19. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

By dawn (violet), 2024, oil on linen, cm 20 x 40. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano

By dawn (violet), 2024, oil on linen, cm 20 x 40. Ph. Sebastiano Luciano -

Too late, 2023, oil on linen, cm 120 x 50, ph. Sebastiano Luciano

Too late, 2023, oil on linen, cm 120 x 50, ph. Sebastiano Luciano