Tomoe Hikita | Just like helium: curated by Davide Ferri

z2o Sara Zanin takes pride in presenting Just like helium, the gallery’s first solo exhibition of the works of Tomoe Hikita, curated by Davide Ferri.

Nell’aria

di Davide Ferri

Scrivo questo testo di sala appena dopo che l’allestimento della mostra di Tomoe Hikita da Z2O, la prima dell’artista in galleria, è terminato. Cosa si può dire di una mostra così a caldo? Ma in fondo – mi chiedo – che cos’è un testo di sala se non un esercizio di ricapitolazione, diciamo così, di alcuni dei fili conduttori che hanno portato alla realizzazione di una mostra? E a cosa serve se non a condividere con lo spettatore delle emozioni provate a caldo?

Inizierei da qui: Tomoe Hikita è nata in Giappone, ma vive a Norimberga da diversi anni. Strana città, forse una delle più grevi e austere tra quelle tedesche che ho visitato. In controluce, la memoria del processo e dei bombardamenti pesanti che lo precedettero. Poi cielo sempre plumbeo, e locali che chiudono presto la sera. E allora: che ci fa Tomoe a Norimberga? Certo, ci ha studiato, ma la sua pittura è quanto di più lontano ci possa essere dal paesaggio che le sta attorno. Ma non è proprio questo che fa un pittore? Chiudere le finestre del suo studio e farvi spuntare dentro un altro mondo? A dir la verità le finestre dello studio di Tomoe sono sempre aperte. E qualche volta lei sale sul tetto del palazzo dove si trova il suo studio e guarda dall’alto la periferia, di fabbriche e di edifici grigi. Mi ha detto che le piace la città da quel punto di vista.

Conosco poco Tomoe – sono andato a trovarla un paio di mesi fa, il nostro dialogo poggiava su basi incerte (lei parla un ottimo tedesco e io tedesco non lo parlo). Però abbiamo sorriso molto, e mi sono accorto che, via via che Tomoe mi mostrava i lavori che aveva preparato per la mostra, non c’era assolutamente bisogno di parole. “My most recent works have become simpler and more drawing-like. There is no particular statement in each work. What’s interesting is that as an artist I don’t explain the work…”, ha detto una volta.

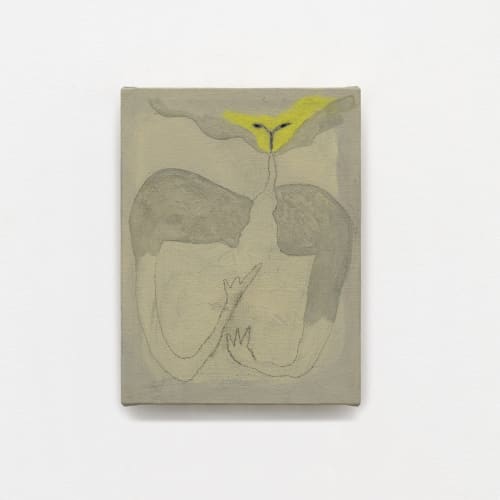

Questa mostra parte dalle immagini. Nella pittura di Tomoe Hikita ci sono prima di tutto le figure che ritornano nel suo lavoro. Così la si può percorrere anche seguendo i fili narrativi tra un dipinto e l’altro, pur sottili: ci sono in mostra, ad esempio, diversi nudi femminili, ermetici ed eterei nello stesso tempo, tradotti con contorni e segni semplici e dimessi, in modo essenziale ed evanescente, a cui l’artista si è dedicata nell’ultimo periodo. E accanto a queste figure femminili delicatamente lascive, prosperose ed enigmatiche, che sembrano intrattenere un contatto esclusivo con il mondo naturale (un naturale espresso in modo semplice, con nuvole, fiori, alberi e piante, ma anche fiotti e zampilli, escrescenze del paesaggio, forme più difficilmente nominabili), ci sono animali dall’aspetto un po’ mostruoso, fantasy. Vagamente deformi. Metamorfici. Uno in particolare, una grande antilope con zampe antropomorfe, sembra irrompere nella partitura che la mostra costruisce, irrompere dal fondo della seconda stanza. Lo stesso effetto lo fa un serpentello che l’artista ha dipinto con unico gesto su un fondo monocratico rosa, un gesto semplice che idealmente dal piccolo quadro prosegue sul muro, come potrebbe accadere in questa mostra, sorta di intervento site-specific, ma dal carattere minimo e giocoso (nel momento in cui ci siamo salutati, ieri sera, Tomoe non aveva ancora deciso se l’avrebbe effettivamente fatto).

In mostra ci sono anche alcuni paesaggi. Waiting in vain, ad esempio, è un’immagine di alberi mossi dal vento resi con campiture oblique, pennellate e tratteggi diagonali e diseguali, che circoscrivono un vuoto centrale, come una lacuna o un buco nel paesaggio. Lo stesso si può dire di Untitled (2023), dove una serie di pennellate liquide, verticali, curve, a destra e a sinistra dell’immagine, sembrano farci vedere da dentro (dall’interno di una grotta o di un antro), e aprire la visione su un vuoto centrale.

Questa capacità di gestire il vuoto, di sospendere l’immagine in uno stato di provvisorietà che ha a che fare con il vuoto, o di farlo diventare elemento costitutivo della rappresentazione, incorniciandolo con poche pennellate, essenziali e solo vagamente riconducibili al reale, al limite del decorativo, mi sembra uno dei tratti più orientali – più giapponesi, diciamo così – di Hikita (che invece tende a essere evasiva sulle sue origini preferendo parlare dei pittori che ama di più, che sono europei: Matisse, Morandi…).

Punta Sabbioni, un altro paesaggio, non è invece niente più che una marina. L’artista l’ha realizzato mentre era in viaggio nei dintorni di Venezia, guardando il mare. Nel dipinto è rappresentato un tendone, ma è più che altro un rettangolo storto e irregolare, che inquadra una porzione di mare; una struttura pericolante, precaria, mossa da un’aria, da un vento, che in mostra sembra soffiare da tutte le parti, e in direzioni contrarie.

A questo vento, a quest’aria, rimanda in fondo il titolo della mostra, che è anche quello di uno dei lavori esposti, Just like helium. Rappresenta una figura dal carattere mercuriale, passeggera ed effimera, leggera come l’elio appunto, disegnata su un fondo di pennellate senza pretese, tracciate con nonchalance, come scarabocchi o cancellature.

In mostra c’è un'altra figura, dipinta nel lavoro dal titolo The child of rain and earth, che abbiamo deciso di collocare più in basso, quasi a filo con il pavimento per evidenziarne il carattere ammaccato o schiacciato. Mostra un bambino steso a terra, colpito da una pioggia violenta (la forza di questa pioggia è sottolineata dai buchi con cui l’artista ha forato e ferito la tela). Ecco, questa figura maschile, in una mostra di figure femminili in dialogo con un naturale fantastico, mi sembra l’escluso, colui che non può essere parte del sistema di relazioni, pur flebili e volatili, che la mostra traccia. Lo guardo, e quell’immagine di ragazzo tramortito dalla pioggia mi pare semmai idealmente riverberarsi nell’immagine rappresentata in un altro dipinto (Untitled, 2024): una pianta secca, afflosciata a terra, su cui veglia una donna in atteggiamento di preghiera. Questo lavoro, dipinto a carboncino su un fondo monocromatico, come molti altri, evidenzia un aspetto nodale della pratica di Hikita: quello di disegnare la pittura – certo, un segno sottile e tremolante, sincopato, a carboncino oppure più fluido, spesso e pastoso, tracciato col pennello – ma solo dopo aver preparato, per questo disegno, un fondo monocromatico o di libere pennellate e campiture. È quello che accade anche in Untitled (2024), il più grande dei dipinti in mostra: una figura femminile che pare adagiarsi in un paesaggio di nuvole e vento, deformandosi e adattando la postura del suo corpo al movimento di pennellate multidirezionali e instabili. Un corpo nell’aria, appunto.